James Fenimore Cooper - A Stan Klos Biography

James

Fenimore Cooper

1789--1851

Edited

Appleton's American Image Copyright©

2001 by StanKlos.comTM

Click

Here for Steel Engraving of James Fenimore Cooper

COOPER,

James Fenimore, author, born in Burlington, New

Jersey, 15 September 1789; died in Cooperstown, New York, 14 September 1851. On

his father's side he was descended from James Cooper, of Stratford-on-Avon,

England, who immigrated to

America in 1679 and made extensive purchases of land from the original

proprietaries in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. He and his immediate descendants

were Quakers, and for a long time many of them remained on the lands thus

acquired. His mother, Elizabeth Fenimore, was of Swedish descent, and this name

too is of frequent occurrence among the Society of Friends in the old Quaker

settlements. Cooper was the eleventh of twelve children, most of whom died

early. Soon after the conclusion of the revolutionary war William Cooper became

the owner of a tract of land, several thousand acres in extent, within the

borders of New York state and lying along the head-waters of the Susquehanna

river. He encouraged the settlement of this tract as early as 1786, and by 1788

had selected and laid out the site of Cooperstown, on the shore of Otsego lake.

A dwelling-house was erected, and in the autumn of 1790 the formidable task was

undertaken of transporting a company of fifteen persons, including servants,

from the comparative civilization of New Jersey to the wilderness of central New

York. The journey was accomplished on 10 November and for six years the family

lived in the log-house originally constructed for their domicile.

Autograph Courtesy of Estoric.com

In

1796 Mr. Cooper determined to make his home permanently in the town he had

founded, which by that time promised to become a thriving settlement. He began

the construction of a mansion, completed in 1799, which he named Otsego Hall,

and which was for many years the manor-house of his own possessions, and by far

the most spacious and stately private residence in central New York. To every

reader that has fallen under the spell of Cooper's Indian romances, the

surroundings of his boyhood days are significant. The American frontier prior to

the 19th century was very different from that which exists at present. Then the

foremost pioneers of emigration had barely begun to push their way westward

through the Mohawk valley, the first available highway to the west. Out of the forest that bordered the shores of Otsego lake

and surrounded the little settlement, Indians came for barter, or possibly with

hostile intent, and until young Cooper was well advanced toward manhood the

possibility of an Indian raid was by no means remote. The Six Nations were still

strong enough to array a powerful band of warriors, and from their chieftains

Cooper, no doubt, drew the portraits of the men that live in his pages. Such

surroundings could not but stimulate a naturally active imagination, and the

mysterious influence of the wilderness, augmented subsequently by the not

dissimilar influence of the sea, pervaded his entire life.

The

wilderness was his earliest and most potent teacher, after that the village

school, and then private instruction in the family of the Rev. J. Ellison, the

English rector of St. Peter's Episcopal Church

in Albany. This gentleman was a graduate of an English University, an

accomplished scholar, and an irreconcilable monarchist. It is to be feared

that the free air of the western continent did not altogether counteract the

influence of his tutor during the formative period of the young American's mind.

As an instructor, however, Ellison was, undeniably, well equipped, and such

teachers were, in those days, extremely rare. His death, in 1802, interrupted

Cooper's preparatory, studies, but he was already fitted to join the freshman

class at Yale in the beginning of its second term, January 1803. According to

his own account, he learned but little at College. Indeed, the thoroughness of

his preparation in the classics under Ellison made it so easy for him to

maintain a fair standing in his class that he was at liberty to pass his time as

pleased him best. His love for

out-of-door life led him to explore the rugged hills northward of New Haven, and

the equally picturesque shores of Long Island sound probably gave him his first

intimate acquaintance with the ocean. No doubt all this was, to some extent,

favorable to the development of his sympathy with nature" but it did not

improve his standing with the College authorities. Gradually he became wilder in

his defiance of the academic restraints, and was at last expelled, during his

third year. Perhaps, if the faculty could have foreseen the brilliant career of

their unruly pupil, they would have exercised a little more forbearance

in his case. Be this as it may, the father accepted the son's version of the

affair and, after a heated controversy with the College authorities, took him

home.

The

United States already afforded a refuge for the political exiles of Europe, and

was beginning also to attract the attention of distinguished foreign visitors;

and many of these found their way as guests to Otsego hall. Talleyrand was among

them, and almost every nationality

of Europe was represented either among the permanent settlers of the town or

among transient sojourners. Young

Cooper, however, did not linger long at home, and, as the merchant marine

offered the surest stepping-stone to a commission in the navy (the school at

Annapolis not being yet established), a berth was secured for him on board the

ship" Sterling," of Wiscasset, Maine, John Johnston master. She sailed

from New York with a cargo of flour bound for Cowes and a market, in the autumn

of 1806, about the time when Cooper should have been taking his degree with the

rest of his classmates at Yale. He shipped as a sailor before the mast, and,

although his social position was well known to the captain, he was never

admitted to the cabin. A stormy voyage of forty days made a sailor of him before

the "Sterling" reached London. During her stay there, Cooper made good

use of his time, and visited everything that was accessible to a young man in

sailor's dress, in and about the city. The "Sterling" sailed for the

straits of Gibraltar in January 1807, and, taking on board a return cargo, went

back to London, where she remained several weeks. In July she cleared for home,

and reached Philadelphia after a voyage of fifty-two days.

According

to the requirements of the time, Cooper was now qualified to be a midshipman ;

his commission was issued 1 January 1808, and he reported for duty to the

commandant at New York, 24 February Apparently war with Great Britain was

imminent, and preparations were made in anticipation of immediate hostilities.

Cooper served for a while on the "Vesuvius," and in the autumn

was ordered to Oswego, New York, with a construction-party, to build a brig for

service on Lake Ontario. Early in the spring of 1809 the vessel was launched,

but by that time peaceful counsels had prevailed, and war was postponed for

three years. All these experiences tended to develop the future novelist.

Many incidents of the stormy North Atlantic voyages appear in his sea novels,

while the long winter on the shore of Ontario gave him glimpses of border life

in a new aspect, and his duties in the ship-yard made him familiar with every

detail of naval construction. After a visit to Niagara, he was left in charge of

the gun-boat flotilla on Lake Champlain, where he remained during the summer,

and on 13 November 1809, was ordered to the "Wasp," under

command of Captain James Lawrence. Nearly two years passed, of which there is

but scant record; but during this period he had become engaged to a daughter of

John Peter De Lancey, of Westchester county, New York, and they were married on

1 January 1811. Here again fate placed him under influences that shaped his

future career. The De Lanceys were Tories during the revolutionary war, and the

family traditions naturally supplemented the teaching of the English tutor.

Cooper's own patriotism was staunch, but the associations of his life were such

that, to a generation that looked with suspicion upon everything English, his

motives often seemed questionable. The marriage was happy in every respect. In

deference to the wishes of his wife, he resigned his commission in the navy on 6

May 1811. After a temporary residence in Westchester county, he went to

Cooperstown and began a house, which was left unfinished and was burned in 1828.

Again, out of consideration for his wife's preferences, he returned to

Westchester county, where he remained until after his first literary success in

1821-'2. In the mean time his parents had died, his father in 1809 and his

mother in 1817; six children, five daughters, and a son had been born to him;

and his time had been given to the cultivation and improvement of his estate in

Scarsdale, known as the Angevine farm. A second son, Paul, was born after his

removal to New York City.

He

was now thirty years old, and seemed no nearer to a literary life than he had

been when he first donned his midshipman's uniform. One day he was reading an

English novel to his wife, and casually remarked, as many another has done under

like circumstances, "I believe I could write a better story

myself." Encouraged by her, he made the attempt, with what ultimate

success the world knows. "Precaution," a novel in two volumes,

was published anonymously in an inferior manner in New York in 1820. Of this

first novel it need only be said that it dealt with high life in England, a

subject with which the author was personally unfamiliar, save through the pages

of fiction. The book was republished in better editions, both in this country

and in England ; and it is noteworthy that the English reviewers gave it a

fairly favorable reception without suspecting its American origin. This venture

can scarcely be said to have enabled him to taste the sweets of authorship, but

it had the effect of stimulating the desire to write. Its modest success was

such that Charles Wilkes and other friends urged him to try some familiar theme.

" If," they urged, "he could so well dramatize affairs

of which he was totally ignorant, why should not the sea and the frontier afford

far more congenial themes ?"

The

story of a spy, related by John Jay years

before, recurred to his memory, and the surroundings of his home Westchester

county, the debatable ground of both armies during almost the whole

revolutionary period furnished a convenient stage. "The Spy"

was the result, and during the winter of 1821-'2 the American public awoke to

the fact that it possessed a novelist of its own. The success of this book,

which was unprecedented at the time in the meager annals of American literature,

determined Cooper's career; but, leaving his subsequent writings for

consideration by themselves, the story of his life is here continued,

independently of his authorship.

In

1823 he was living in New York. There, on 5 August his youngest child, Fenimore,

died, and Cooper himself was shortly afterward seriously ill. By 1826 his

popularity had reached its zenith with the publication of the "Last of

the Mohicans." Until this time he had always signed his name James

Cooper; but, in April 1826, the legislature passed an act changing the family

name to Fenimore-Cooper, in compliance with the request of his grandmother, who

wished thus to perpetuate her own family name. At first Cooper attempted to

preserve the compound surname by using the hyphen, but he soon abandoned it

altogether. With fame had arisen envy and uncharitableness at home and abroad.

English reviewers at once claimed him as a native, and stigmatized him as a

renegade. His birthplace was, with much show of authority, fixed in the Isle of

Man, and for many years the matter was seriously in dispute, notwithstanding the positive proofs of his American

nativity. In the decade following the adoption of his mother's surname the

controversies gathered force that affected the closing years of his life, and

even survived him.

He

was one of the first Americans that, from personal association, reached a point

whence he could look without bias upon the somewhat crude social development of

his native country. Naturally of a headstrong and combative disposition, he had

not the address to temper his utterances so as to avoid giving offence in an age

when the popular sense smarted under what Mr. Lowell, even in our own time, has

termed "a certain condescension in foreigners." All his

patriotic championship of the young republic in foreign lands counted for naught

in the light of the criticisms pronounced at home. His self-assertive manner

made him enemies among men who could not understand that he was merely in

earnest, and even Bryant owned to having been at first somewhat startled by an "emphatic

frankness," which he afterward learned to estimate at its true value. A

thorough democrat in his convictions, Cooper was still an aristocrat, and he

often gave expression to views under different conditions that seemed alike

contradictory and offensive. His love of country, however, was one of the most

pronounced traits of his nature, and his faith in what is known as the "manifest

destiny" of the republic was among the firmest of his convictions. This

faith remained through the troublous days of "nullification," and

through the early controversies concerning the abolition of slavery. Abroad he

was the champion of free institutions, and had his triumphs in foreign

capitals.

At

home he was looked upon as an enemy of all that the fathers of the republic had

fought for. An English writer in Colburn's "New Monthly Magazine"

(1831) said of his personal bearing: "Yet he seems to claim little

consideration on the score of intellectual greatness; he is evidently prouder of

his birth than of his genius, and looks, speaks, and walks as if he exulted more

in being recognized as an American citizen than as the author of ' The Pilot'

and ' The Prairie.'" This proud Americanism did not, however, after the

first years of his celebrity, injure his standing in England. During his

repeated and often protracted visits to England, his society was sought by the

most distinguished men of the time, although it is said that he never presented

letters of introduction. He very soon convinced those with whom he associated

that, though an American, he was not an easy person to patronize. On the

continent he was unwillingly led into a controversy to which he ascribed much of

the unpopularity that he afterward incurred in the United States. A debate had

arisen in the French chamber of deputies in which Lafayette

referred to the government of the United States as a model of economy and

efficiency. Articles soon appeared in the papers disputing the accuracy of the

figures, and arguing that the limited monarchy was the cheapest and best form of

government.

Cooper,

after holding aloof for a time from the discussion, published a pamphlet

prefaced by a letter from Lafayette to himself, in which he reviewed the whole

subject of government expenditure in the United States. This provoked answers

and contradictory statements, some of which had a semi-official origin in the

United States legation at St. Petersburg. One immediate outcome of the affair

was a circular from the department of state calling for information regarding

local expenditures. Against this Cooper protested in a long letter, which was

published in the "National Gazette," of Philadelphia. The

letters on the finance discussion aroused what now seems an altogether

inexplicable bitterness against their author. The attacks upon him in the

newspapers were excessively annoying to a proud and sensitive nature, and when

he returned in 1833 it was with a determination to abandon literature, and a

distrust of public opinion under the American republic. He resolved to reopen

his ancestral mansion at Cooperstown, now long closed and falling into decay,

and visited the place in June 1834, after an absence of nearly sixteen years.

Repairs were at once begun, and the house was speedily put in order.

At

first the winters were spent in New York and the summers in Cooperstown ; but

eventually he made the latter place his permanent abode. He was no longer in

sympathy with the restless spirit of progress that had exterminated the Indian

and was leveling the forests of the United States. The Mohawk valley, once

traversed only by a rude bridle-path, now afforded passage for an endless

procession of canal-boats from the ocean to the inland seas; railroads were

building, and the whole motive of existence was feverish anxiety for gain. The

associations of his boyhood home soon revived the instinct for literary work,

and he resumed his pen. But in the mean time he did not hesitate to express his

conviction that the morals and manners of the country were decidedly worse than

they had been twenty years before, and the utterances of so famous a man soon

became public property. A contemporary journal said of him, in 1841: "He

has disparaged American lakes, ridiculed American scenery, burlesqued American

coin, and even satirized the American flag!" Cooper had apparently

believed that his amicably intended criticism of American manners and customs

would be received with some deference, if not with a moderate degree of

gratitude, and vituperation of this character astonished him. During the years

that followed, the breach steadily widened between Cooper and his countrymen,

and even his fellow-towns-men.

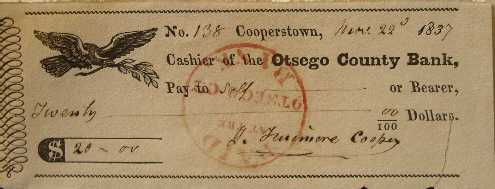

In

1837 the local quarrel culminated in what was known as "the

three-mile-point controversy." This point was a part of the Cooper

estate, and, owing to the good nature of the heirs, had been used as a public

resort until the townspeople had come to believe that it was actually their own.

When Cooper returned to his home he endeavored, in an informal way, to uproot

this idea of public ownership. Each repetition of his purpose was resented, and

at last a popular outcry was raised against the arrogant claims of "one

J. Fenimore Cooper." A Massachusetts-meeting was called, and fiery

resolutions were passed; but there was not a shadow of lawful right on the

popular side, and, as soon as measures were taken to protect the property

against trespassers, the claim of the town had to be abandoned. The affair,

however, widened the breech between the author and the public, and the

newspapers were not slow to present his actions to their readers in the most

objectionable light. The novel entitled "Home as Found" was an

outgrowth of this experience a sequel, nominally, to "Homeward

Bound," but as different as possible in most of the qualities that go

to make a successful novel. Cooper's indignation appears to have dulled his

literary discrimination, and he made the characters in his novels express

unpardonably offensive ideas in the most disagreeable way imaginable. Two of

these characters were identified as intended to personate the author himself

John and Edward Effingham in "Home as Found " and none of the

protests and denials put forth by Mr. Cooper had any appreciable effect in

removing the impression. For writing this book he was never forgiven by his

contemporaries, and the bitterness of popular indignation was intensified by the

knowledge that the book, like his others, was sure to be translated into all the

languages of Europe. On the other hand, the brutality of the newspaper attacks

upon the author was inexcusable.

During

the decade ending with 1843 Cooper explored almost every available avenue to

unpopularity, not only in his own country, but in England. Even such professedly

exemplary and fastidious publications as Blackwood's and Frazer's magazines

invented epithets in worst taste, if possible, than those applied to him in his

own country. Just at this crisis, when he was denounced in England for obtrusive

republicanism, and pursued at home for aristocratic sympathies, he instituted

libel suits against many of the leading Whig editors in the state of New York. Among these was Thurlow

Weed, of the Albany "Evening Journal," James Watson Webb,

of the " Courier and Enquirer," Horace

Greeley, of the "Tribune," and William L. Stone, of the "Commercial

Advertiser," the three last-named journals published in New York City.

These suits at first caused much merriment among the defendants; but when jury

after jury was obliged, in most cases, reluctantly to return a verdict for the

plaintiff, there was a decided change in the tone of the press. The damages

awarded were usually small, but the aggregate was considerable, and the

restraining effect of verdicts was immediately apparent. The suit against Mr.

Webb differed from the rest, in that it was a criminal proceeding, under an

indictment from the grand jury of Otsego county. Probably Mr. Cooper failed to

secure a verdict in this instance for the reason that, while the jury might

probably have assessed damages, they could not agree to send the defendant to

prison. Possibly, however, the reading aloud in open court by plaintiff's

counsel of "Home as Found" had an unfortunate effect. In these

suits Mr. Cooper acted as his own counsel, with regular professional assistance,

and proved himself an able advocate and an excellent jury-lawyer. The most

pertinacious of the accused journalists was Thurlow Weed, and against him

numerous distinct and successful suits were brought. Repeated adverse verdicts,

with costs, at last reduced even Mr. Weed to submission, and in 1842 he

published a sweeping retraction of all that he had ever printed derogatory to

Cooper's character. These successful prosecutions did not in the least help the

author's general popularity. Indeed, he seemed to undertake them in a spirit of

knight-errantry, and follow them to the end from a lofty conviction of the

righteousness of his own cause. The effect of the controversy was to embitter

the last years of a life that should have ended serenely in the assurance of a

well-earned and world-wide literary fame.

Cooper

died in his home, Otsego Hall, and was buried in the Episcopal Church-yard.

A monument has been erected there, surmounted by a statue of "Leather-stocking,"

and bearing as a sufficient inscription the author's name in full, with the

dates of his birth and death. Six months after his death a public meeting was

held, in honor of his memory, in the city of New York. Daniel

Webster presided and addressed the assembly, as did also William Cullen

Bryant. Washington Irving was

also present, with a large representation of the most cultivated people in the

city. A few years after the novelist's death Otsego Hall was burned, and the

surrounding property was sold by the heirs. In concluding a sketch of Cooper's

life, it should be said that when about to die, and apparently in the full

possession of his faculties, he enjoined his family never to allow the

publication of an authorized account of his life. This command has been

faithfully obeyed, and none of the several biographers have had access to his

papers. Mrs. Cooper survived her husband only a few months, and was buried by

his side at Cooperstown.

An

exhaustive history of Cooper's literary work would include more than seventy

titles of books and other publications, and a long list of miscellaneous

articles published in magazines and newspapers. Some of these have been casually

referred to in the preceding narrative, when they seemed to mark important

passages in his career. Such were "Precaution," his first

venture, "The Spy," his first success, "The Last of the

Mohicans," marking the high tide of his popularity, and "Home

as Found," as the direct cause of the unhappy final controversies. The

ten years following the publication of "The Spy" saw perhaps

his chief successes. These included the five famous "Leatherstocking

Tales," beginning with the " Pioneers," of which 3,500

copies were sold before noon on the day of publication. This period also

included "The Pilot," the production of which was suggested by

the appearance of Scott's "Pirate," which, in Cooper's

estimation, was unmistakably a landsman's work. Cooper's sailor instincts told

him that the most had not been made out of the available materials, and he was

successful, in this and his other sea-stories, in proving his theory. "Lionel

Lincoln," too, was the first of a distinctive group intended to

embrace, as the title-page to the first edition indicated, "Legends of

the Thirteen Republics." After the summit of fame had been reached, and

his books were eagerly awaited in two continents, came the controversial period,

extending to 1842, and overlapping by a year or more the last decade of his

literary activity. It was inevitable that the disturbing influences preceding

his later work should have their effect. An observer so keen as he could not

fail to note the position in which he had been placed by the misunderstandings

and disputes that had fallen to his lot. The younger generation of readers had

almost insensibly imbibed the impression that he was the justly disliked and

distrusted critic of everything American. That he was conscious of this feeling,

and sensitive to it, is evident from passages in the later works, in which he

alludes to love of country and popular injustice, and the like. This period also

saw the production of his "History of the United States Navy," a

work for which it is said he had been collecting materials for as many as

fourteen years. For its preparation he was peculiarly qualified, through his

personal acquaintance with naval officers and his familiarity with all the

details of a seafaring life. When it is read at this late day it is difficult to

understand why it should have excited the rancor that it did. Any one of the

present generation who is reasonably fair-minded must see that it is the work of

a judicial mind, which seeks to do exact justice, irrespective of patriotic

considerations. It was its fate, however, to stir up controversies as harsh and

enduring as any of those in which its author was previously engaged, and it was

freely denounced on both sides of the ocean as grossly unfair for diametrically

opposite reasons. Cooper's facts have borne the test of time, and the work must

always remain an authority on the subject treated. It was highly successful

commercially, and went through three editions before the author's death, which

event interrupted a continuation of the work intended to include the Mexican

war. As one of the most successful of authors, Cooper's fame is assured. The

generation that now reads the "Leatherstocking Tales," "The

Pilot," " Wing and Wing," and the rest of his stories of

adventure, know him only as a master of fine descriptive English, with a

tendency now and then to prolix generalization. His libel suits and

controversies are forgotten, his offensive criticisms are rarely read, and he is

remembered only as the most brilliant and successful of American novelists.

The

greater part of Cooper's title-pages, in the original editions at least, do not

bear his name. They are "by the author of, etc., etc." The

controversial papers usually bore his name. In the " Knickerbocker,"

"Graham's," and the "Naval" magazines and

elsewhere, he published many valuable contributions, letters, and some serial

and short stories that afterward appeared in book-form. Several posthumous

publications appeared in "Putnam's Magazine" A work on "The

Towns of Manhattan" was in press at the time of his death, but a fire

destroyed the printed portion, and only a part of the manuscript was recovered.

A few books have been erroneously ascribed to him, but they are not of

sufficient importance to be now mentioned. The following list embraces all his

principal works : "Precaution," a novel (New York, 1820;

English edition, 1821); "The Spy, a Tale of the Neutral Ground"

(1821 ; English edition, 1822); "The Pioneers, or the Sources of the

Susquehanna ; a Descriptive Tale" (1823 ; English ed., and London,

1823); "The Pilot, a Tale of the Sea" (1823);" Lionel

Lincoln, or the Leaguer of Boston" (1825) ; "The Last of the

Mohicans, a Narrative of 1757" (Philadelphia, 1826); "The

Prairie, 'a Tale" (1827) ; "The Red Rover, a Tale"

(1828) ; "Notions of the Americans ; Picked up by a Travelling

Bachelor" (1828); " The Wept of Wishton-Wish, a Tale"

(1829); English title, "The Borderers, or the Wept of Wishton-Wish,"

also published as " The Heathcotes" ; "The Water-Witch,

or the Skimmer of the Seas; a Tale " (1830) ; "The Bravo, a

Tale" (1831) ; "Letter of J. Fenimore Cooper to General

Lafayette on the Expenditure of the United States of America" (Paris,

1831); "The Heidenmauer, or the Benedictines; a Legend of the

Rhine" (Philadelphia, 1832); "The Headsman, or the Abbaye des

Vignerons; a Tale" (1833); "A Letter to his Countrymen" (New

York, 1834) ; "The Monikins" (Philadelphia, 1335) ;

"Sketches of Switzerland" (1836); English title, "Excursions

in Switzerland";" A Residence in France, with an Excursion up

the Rhine, and a Second Visit to Switzerland "; " Gleanings in

Europe" (1837) ; English title, " Recollections of Europe

"; " Gleanings in Europe-England" (1837) ; English

title, "England, with Sketches of Society in the Metropolis";

" Gleanings in Europe-Italy" (1838) ; English title, "Excursions

in Italy "; " The American Democrat, or Hints oil the Social

and Civic Relations of the United States of America" (Coopers-town,

1838); "The Chronicles of Cooperstown" (1838); "Homeward

Bound, or the Chase; a Tale of the Sea" (Philadelphia, 1838); "Home

as Found" (Philadelphia, 1838); English title, "Eve Effingham,

or Home"; "History of the Navy of the United States of America" (1839);"

The Pathfinder, or the Inland Sea" (1840), "Mercedes of

Castile, or the Voyage to Cathay" (1840); English title, "Mercedes

of Castile, a Romance of the Days of Columbus"; " The Deerslayer, or

the First War Path ; a Tale " (Philadelphia, 1841); " The Two

Admirals, a Tale" (1842) ; "The Wing-and-Wing, or Le Feu-Follel;

a Tale" (1842); English title, "The Jack o' Lantern (Le

Feu-Follet), or the Privateer "; "Richard Dale" ;

"The Battle of Lake Erie, or Answers to Messrs. Burges, Duer, and

Mackenzie" (Cooperstown, 1843) ; " Wyandotte, or the Hutted

Knoll; a Tale" (Philadelphia, 1843);" Ned Myers, or a Life

before the Mast" (1843); "Afloat and Ashore, or the Adventures

of Miles Wallingford" (published by the author, 1844; 2d series, New

York, 1844; English title, "Lucy Hardinge ") ; "

Proceedings of the Naval Court-Martial in the Case of Alexander Slidell

Mackenzie, a Commander in the Navy of the United States, etc., including the

Charges and Specifications of Charges preferred against him by the Secretary of

the Navy, to which is anhexed an Elaborate Review" (1844);"Satanstoe,

or the Littlepage Manuscripts; a Tale of the Colony" (1845) ; "The

Chainbearer, or the Little-page Manuscripts" (1846) ; "Lives of

Distinguished American Naval Officers" (Philadelphia and Auburn, 1846);

" The Redskins, or Indian and Injin ; being the Conclusion of the

Littlepage Manuscripts" (New York, 1846); English title, "

Ravensnest, or the Redskins" ; "The Crater, or Vulcan's Peak ;

a Tale of the Pacific" (New York, 1847); the English title was "Mark's

Reef, or the Crater"; "Jack Tier, or the Florida Reefs"

(1848) ; "The Oak Openings, or the Bee Hunter" (1848); English

title, "The Bee Hunter, or the Oak Openings"; "The Sea

Lions, or the Lost Sealers" (1849) ; "The Ways of the Hour ; a

Tale" (1850). See "Memorim Discourse" by William

Cullen Bryant, with speeches by Daniel Webster and others (New York, 1852); "

The Home of Cooper," by R. born Coffin (Barry Gray) (1872); "James

Fenimore Cooper," by Thomas Rainsford Lounsbury (Boston, 1882); and "Bryant

and his Friends" (New York, 1886).

His

daughter, Susan Fenimore Cooper,

author, born in Scarsdale, New York, in 1813, is the second child and the eldest

of five that reached maturity. During the latter years of her father's life she

became his secretary and amanuensis, and but for her father's prohibition would

naturally have become his biographer. In 1873 she founded an orphanage in

Cooperstown, and under her superintendence it became in a few years a prosperous

charitable institution. It was begun in a modest house in a small way with five

pupils; now the building, which was erected in 1883, shelters ninety boys and

girls. The orphans are taken when quite young, are fed, clothed, and educated in

the ordinary English branches, and when old enough positions are found for them

in good Christian families. Some of them before leaving are taught to earn their

own living. In furtherance of the work to which she has consecrated her later

years, and which she terms her "life work," during 1886 she

established "Tho Friendly Society." Every lady on becoming a

member of the society chooses one of the girls in the orphanage and makes her

the object of her special care and solicitude. Her home is built mainly with

bricks and materials from the ruins of Otsego Hall, of which a fine view is

given on a previous page. Her published books are "Rural Hours" (New

York, 1850); "The Journal of a Naturalist," an English book, edited

and annotated by Miss Cooper (1852); " Rhyme and Reason of Country

Life" (1885); and "Mt. Vernon to the Children of America" (1858).

-- Edited Appleton's Cyclopedia

American Biography Copyright©

2001 by StanKlos.comTM